How Do I Use Developmental Editing?

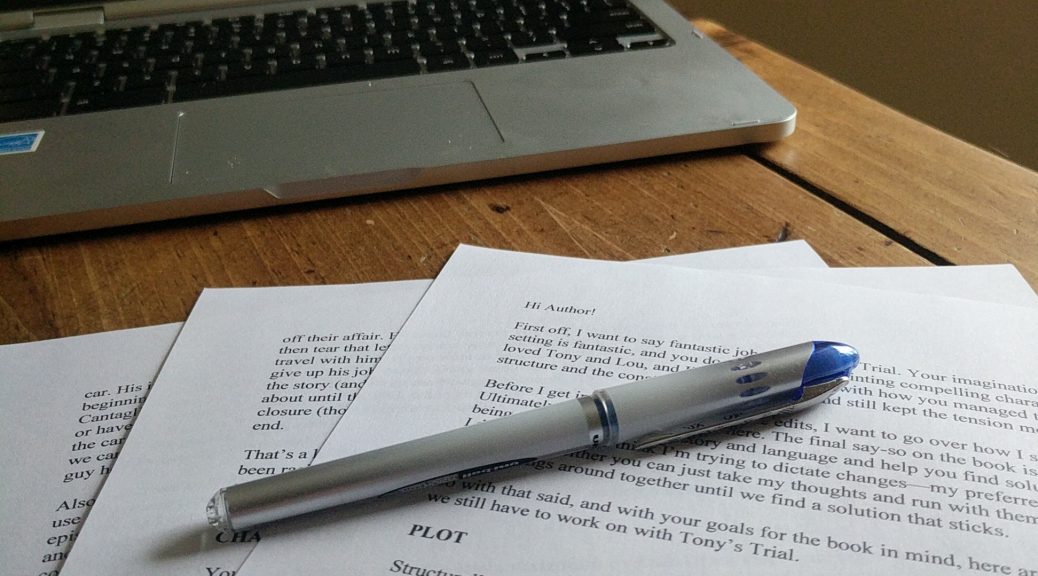

I like to think of developmental editing as having two stages: first, there’s the creation of the edit letter and annotated manuscript that communicate issues or areas for improvement in a book to the writer. Second, there’s revision, where the writer takes the results of their developmental editing and implements them in the book. As a writer and an editor, I’ve participated in both stages, and I’ve developed some guidelines on how to use them.

First, figure out what works.

Most rounds of developmental editing will contain a mixture of feedback that’s instantly useful to the writer and feedback that isn’t. It’s often easiest to start your revision by creating a separate document and listing the revisions that are either simple and quick or light you up and make you excited to get back to work. Many times this covers the bulk of what’s flagged up in a manuscript.

Second, figure out what doesn’t work.

Developmental editing also tends to produce a few suggestions that the writer considers nonstarters. Either the editor misunderstood a central aspect of the story, wanted to push it in a direction the writer felt uncomfortable with, or jumped straight into making suggestions rather than identifying problems and letting the writer create solutions. (Note: This doesn’t mean you got bad editing! It’s an art, and no editor is perfect all the time. Judge your editor based on the overall usefulness of their work.)

Third, wrestle with the hard parts.

Once you’ve eliminated the definite yeses and definite noes, you’re left with the tricky parts. These are often the revisions that most improve the manuscript. Take some time, even if it’s days or weeks, to think through your editor’s comments and suggestions. Usually you’ll end up rejecting some of them and accepting others, and you may find that in this stage the other suggestions made in developmental editing start to link together. A definite-yes revision may lead you to a solution for a tricky problem. Or a definite no may lead you to better understand something essential. Whatever happens, don’t settle on a final revision plan until you’re happy with all the changes you’re going to make, and feel free to contact your editor for extra feedback or kick ideas around with them. A good one will be more than happy to help.

Next, we’ll talk about who does developmental editing. Or you can return to our developmental editing index.